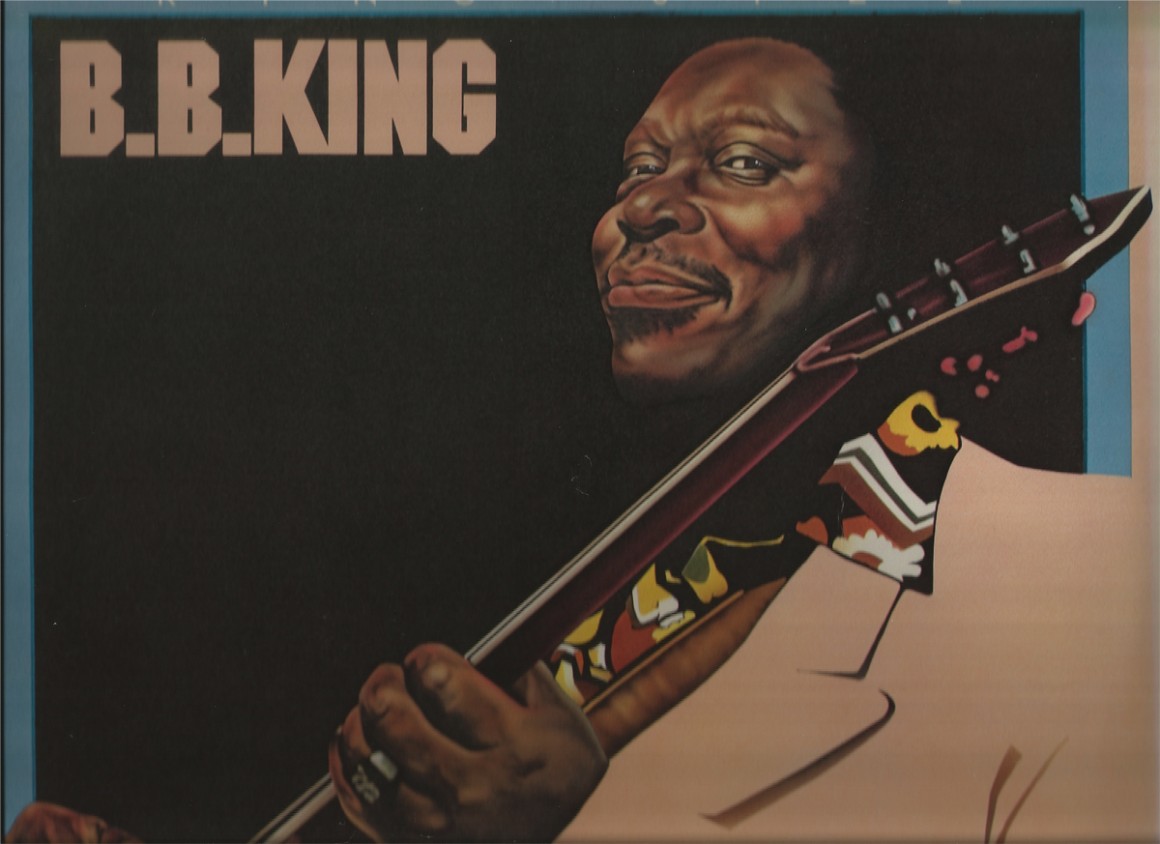

From “Man-Child” to Blues Royalty…. Long Love the King

by TJ Wheeler

The 20 year old Black man in May 1945 was having mixed feelings about his life’s prospects. There was a World War still raging and still another in his inner world. After all, at his young age he had already achieved the coveted position of tractor driver on a share cropping plantation just outside of Indianola Mississippi. He had been drafted, gone through boot camp, but went back home, when given the choice. The Selective service had made a deal with the local plantations that essential workers, such as tractor drivers, could return after boot camp to insure that there would be crops, such as cotton and soy beans for the troops’ clothing and food. He was still in turmoil over that decision. The service, could have been his ticket out of the Jim Crow south (as well as a free, formal education courtesy of the GI bill) on the other hand, he had recently married, he had, for his peer group, a decent job and was out of danger, at least from foreign enemies. The violent, enforcement of segregation and Black codes dictated that he wasn’t free. Sometimes he wondered, whether the pressure of constant self censorship of speech and even body language around Whites, had contributed to his intermittent stutter. When he wasn’t driving tractor, he often took the few chords he knew, on the guitar, and performed playing and singing Blues on the streets. Other times he played and sang with the Famous St. John Gospel Singers. Even with hedging his bets, playing both Blues and Gospel, he still couldn’t survive without that damn tractor.

All day long, in the blistering heat, he’d been driving the tractor, though it felt like the tractor was driving him. Which of the two was hotter was debatable. Hell, it was pay day, and enough was enough. Parking the tractor in the shed, he quickly shut it down, jumped off, still listening more to the dueling voices in his head than the tractor. He had only gone a few feet before he heard the chugging sound that instantly brought him back to reality. He made a bee line back for it, but as he arrived the tractor was already breaking it’s way through the back wall of the shed. He had known better… as the tractor frequently “dieseled” after being turned off and would make post-ignition surges. If he had only listened to his second mind he would have waited patiently as usual making sure the tractor wasn’t going anywhere, let along through anything else.

It hadn’t been that long since the tractor had replaced the mule plowing the fields. As a man-child for four years, for half of each year, six days a week, from “can’t see, ‘till can’t see” he figured he spent a million miles behind a mule’s rear end and he still wasn’t going no where! Back in the day, that ole mule, had to be attended to with greatest of care. If, for instance, that mule was over driven, mistreated, intentionally or not and died, the field worker’s own life, in many a plantation, might be in danger. Simply put in the Jim Crow era doctrine, a mule’s life, most often, was more important than a Black man’s. Now this new mechanical mule, to with which he’d been entrusted had not only been damaged it had ruined the shed. There was no time for deliberation on the matter, and panic told him just one thing….run. He kept running and when he realized he couldn’t outrun the punishment that could be dealt him, he was able to flag down a Lewis Grocery Company food distribution truck. For helping the driver load and unload along the way he earned a ride in the back of the truck, to what he envisioned was heaven on earth, Memphis, Tennessee. Once there, he didn’t stop untill he was in the safety of his older second cousin’s home. Ever since he could remember he always looked forward to his much older relative’s drop-in visits. He marveled at how he would be dressed to the “nines,” pin striped suit, a Stetson hat no less, and most importantly marveled at his guitar playing and singing. Booker T. Washington White’s (AKA Bukka White) Delta Blues had made a deep impression on young Riley. For someone who hadn’t gotten his first pair of long pants ‘till he was a teenager and hadn’t ever been away from Greenwood, Bukka’s high styling clothes, musical talent and perhaps most importantly his independence, gave Bukka “world shaker” status with Riley. If there was anybody that could help him in this time of need it would definitely be him. Maybe he didn’t realize it at the time, but young Riley wasn’t only running from his share cropping farm, he was running to his future.

Though he didn’t have Cousin Bukka’s address, he searched him out on Beale St. though distracted by sights, bright lights, and amazing sounds, he kept asking till he managed to get the directions to his related Bluesman’s home. Not finding his cousin at home, Riley curled up on his door step and fell fast asleep. When he came home later that evening, Bukka brought him in, fed him and listened to this terrified young man’s tale of woe. Patiently he told him to calm down, and realize that he was a man now, and he could either let life dictate to him or he could make up his own mind about what, when, and where, his life would go. In the meantime he told him to get some sleep as he was going to get him a job where his day job was at the Newberry Equipment Company. For eight months Riley stayed with Bukka, worked with him, and followed him around “like a puppy” (as BB wrote in his autobiography Blues All Around Me) to wherever he played.” He’d entertain at a party for 200 with the same enthusiasm as a party of 20.” BB remembered.

Riley tried repeatedly to capture the sound Bukka would get on his “Slide” from his National Steel resophonic guitar. The vocal like phrasing and tremolo effect of the slide mesmerized the still young apprentice, but try as he might he just couldn’t get comfortable with the steel pipe on his fingers and felt clumsy in his attempts. Instead, he, to the best of his efforts, tried to replicate the slide effects with just his left hand fingers. Slowly but surely a very personal, intimate, trill came out of that box, which in a short time would be a huge part of his very own signature sound. Riley, though Black and poor, certainly didn’t live in a vacuum. Radio stations brought the sounds of diverse other influences including Django Reinhart. Django’s Gypsy Jazz had a touch similar to the one Riley was looking for. A trill that was filled with passion, joy, reflection and at times a hint of melancholy.

According to Bukka “Though he was coming on with his music, I could tell that things be still bothering the boy. Before he could go any further with his music and life he needed to go home and set things right with his wife and the mess he made down there with his boss and job.” Bukka also promised him that once he had ridden himself of those burdens he could high tail it back and make a go of it back in the big city of Memphis. Riley followed Booker’s advice to the “T” and a little over two years later, with his wife following shortly after, came back to Memphis …and with the early on help of his cousin, you might say he made quite a go of it.

Riley’s influences kept broadening as deep and wide as the Big Muddy itself. Discovering through the radio Blind Lemon Jefferson, Lonnie Johnson, T Bone Walker, Louie Jordan, Count Basie, Dinah Washington and many, many more. Off the farm, and now in the thick of Memphis’s Beale St., he could take in all the magnificence of live Blues, in all of it’s generational overlapping glory! There, all within a few blocks, you could hear the Memphis Jug Band and the Gus Cannon Jug Band, Memphis Minnie, the upbeat Roscoe Gordon, Sax and Hammond B3 Jazz from Fred Ford, Honeymoon Gardner and of course Rufus Thomas. It was Rufus that said that Beale Streets mojo was so strong “That if a White man spent a Saturday night there….he’d never want to be White again!”

Rufus would go reminding Riley, for the rest of his life, how when Rufus was the MC at the weekly talent contest at the Daisy Theater, the young singer/ guitarist would beg to be included week after week. Riley himself would reflect on that saying he just had to have that extra one dollar bill a week to help make ends meet.

Following Bukka’s advice, he auditioned and was given a 10 min. radio spot on WDIA radio. called the King Spot which later was changed to the “Sepia Swing Club.“ This is where, of course, he began being called 1st; the “Beale St. Blues Boy” then shortened to “Blues Boy King” and then finally B.B. King. There was in Jazz already a Count and a Duke but now the Blues had their anointed King. Not to steal any thunder away from the divine circle of other incredible Kings …such as Freddie, Albert, Earl and Little Freddie….but over the decades, more than any other, it was BB who wore the crown of King of the Blues as well as the Ambassador of the Blues to adoring audiences worldwide.

A display at the Rock ‘n’ Roll Museum in Memphis- with two of BB’s signed guitars and a photo of his orchestra- photo by Diana Shonk

Another key piece of advice Bukka gave Riley ”BB” King was “When you go on stage, make sure you dress like your going to the bank for a loan.” (Bukka said the exact same thing to me after playing our first gig together, (along with Randy Handley ) in Boulder Colorado in 1973. No more overalls on the gig for me after that!)

When I stop to think about it, all of my ties to BB came through Bukka, as well as from some of his legendary sidemen/women and other mentors and influences of his, that I’ve been fortunate enough to play with. I’m sure many avid Blues Audience readers knowledge of BB’s, rivals if not surpasses, my own. For that matter, I know for a fact many of you have your own BB King moment and insights that you could share. That being said I feel the best thing I can add are a few insights drawn from my memories and observations that I gathered through the sources I’ve mentioned.

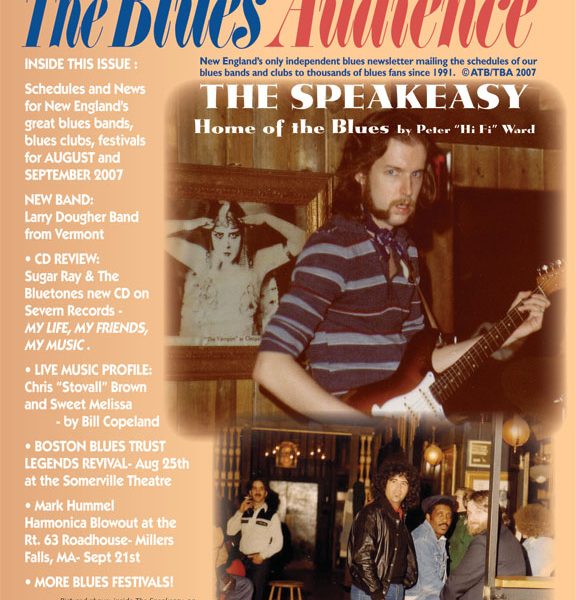

It was 1969 when I first experienced the power of BB King live, performing in a hippie haven called The Eagles Auditorium in Seattle Washington (which was one of the many spin offs of the famed, San Francisco Fillmore Ballroom. Instead of the well worn ”Chitillin Circuit” most Black Bluesmen and women had been traveling for decades, the Fillmore’s producer/musical director Bill Graham, under the prodding of Michel Bloomfield and Paul Butterfield, started booking the overlooked original Black Blues. The very acts that so many of the psychedelic Bay area bands were either derived from, or at least heavily influenced by. Talk about a juxtaposition of cultures!

This was by no means BB’s first time in Seattle . He had played at the Encore Ballroom as well as at several clubs in Seattle’s predominant Black Central district area. His long time devoted African American following came dressed to BB’s Eagle’s gig, as if they had taken directions from Bukka himself…..”like they were going to the Bank for a loan.” Fox furs, “Bling,” Bling dresses and jewelry, shark skin suits, velvet broad brim fedoras, over sized polyester shirt lapels and all looking all of that and then some. Contrasting them was all of us, the regular crowd, dressed in our best tie dye, head bands, love beads, leather vests, and well broken-in holey blue jeans. At first the Black audience members seemed very ill of ease mingling with such shabbily dressed, unkempt, flower children. When BB and his Orchestra (like Duke Ellington and Count Basie…BB had a razor sharp, tightest of tight orchestras….NOT a band…after all we’re talking royalty here) took the stage, all cultural differences seemed to dissipate instantly. BB literally launched, into a high octane version of “Why I sing the Blues” complete with swinging his guitar, “Lucille,” to his side as he snapped his fist repeatedly into the palm of his other hand, emphasizing such lyrics as “I heard the rats tell the bed bugs leave the roaches some!!!” That was the first time I openly cried in public, outside of attending a funeral for a close friend when I was 13. The music was a catharsis. An eclectic Blues gumbo of Mississippi abandonment, combined with the discipline and swing of Kansas city, the soul of Memphis with the passion and total intensity of Gospel, it all came driving home, and hit me like a Mack truck. Though the sound was a totality of every fantastic musician up there, there was no doubt that it would have only been possible through the mind, body and soul of one BB King. The tears that I found were not only tears of joy, they were tears of realizing someone else really understood me. (Speaking of the Orchestra, the almost all Black band had one White musician playing piano. Seven years later I met, that still young piano player, Ron Levy, as he and Johnny Nicholas came and played a set break for Blues piano master Roosevelt Sykes at Sandy’s Jazz Revival, where harmonica player Hatrack Gallagher and I were doing a week of gigs with the one and only “Honeydripper.”

BB put it all together, with only Ray Charles rivaling him for that complete Black American roots musical live show. Even Ray seldom had that commitment to the moment that BB has always had. Ray’s live shows (I have to choose my words VERY carefully here as I am a huge of fan of his) just being Ray… genius, though with repeated listening often seem to resemble each other a little to predictably. One can’t ever be too sure of exactly where BB’s Blues might take him. He has always changed up his sets and even in the same song order they never felt exactly the same, any more than two days feel exactly the same. If a groove jumped up and bit him and Lucille, then the band and the audience were always eager to go follow, just for the wonderful ride. One night about 15 years ago, he was particularly having fun improvising over some back ally grooves and side pocket combination shots and licks to a great audience in a packed hall. He laughed and turned his head over his shoulder to the band and said “ I hope you guys didn’t make any immediate plans for after the show, cause I have a feeling this is going to take a while!” We all cheered and “take you time” was shouted out by several of us back at him.

Every time I’ve ever seen BB (which has been at least 30 times) it was always simultaneously a jubilee, an catharsis, a master class on what and what not to play, and it was always a complete recharging of my batteries, pure inspiration. For decades, if I dropped by BB’s green room, after his concert, just a mention of being a friend and student of Bukka’s to the security guard would grant me a short audience with the King himself. From ‘73–’77 (the latter date being the year Bukka passed) BB was always happy to hear of news about his first mentor. Another night closer to 40 years ago on a wintry night in Denver to a quarter filled, brightly lit auditorium, BB clearly seemed challenged to find those “funny little in between sounds“ that he defined were the real blue notes. Many artists would have been checking their watches, just content to get through the gig, BB however told the small audience “I know Lucille has some Blues in here…but I can’t seem to find them tonight” noticeably more than a little frustrated. He continued saying ”Stick around though, because I know, if I work at it just a little more… they’re going to flowing through.” Though he sounded more like a plumber than a Bluesman, even to my surprise, BB turned the night inside and out and rising above everything he found, with his incredible vocal-like bends and that imitable trill, Lucille’s and the luke warm audience’s sweet spot.

The decade after decade toll of over 300 annual shows slowly decreased his schedule in the 90s to a still unimaginable 250 or so dates of annual concerts, festivals worldwide. With the diagnosis of diabetes, and the effects of the inescapable passage of time, BB started sitting down in the middle of his set. Though at first it alarmed me, I soon was drawn into another side of BB. With only the rhythm section backing him (them also sitting) he relaxed as if he sitting on a easy chair on the front porch of his old home on a warm Mississippi night. For the first time I saw the master just kick back and relax. There was trace of nervousness, let alone a stutter, now the stories combined with the more old school Delta rhythms led him and transported all of us with him to… back in the day. “My God “I thought to myself, this is so much like Bukka, holding court out on Mosby St. reminiscing and just carrying on, I loved it. After about 15 – 20 minutes, the horns would re-enter, BB and the rest of the band would stand back up, and the more urban, higher energy groove would build back up with intensity of what I had literally grown up with.

When he closed we were all on our feet, demanding more, many rushing to the foot of the stage for a hand shake, the lucky ones getting an official BB King guitar pick and before finally leaving bowing and waving to us all his heartfelt appreciation of us. If the audience worked it long and hard enough, often he’s come back for an encore. Most often the one or two songs would include Please accept my love. Accept his love? We continue to survive on it.

The “sit down” portion of the show eventually turned in the majority of the time on stage. But the inspiration, and unconditional love never stopped even for an instant. Maybe with the outpouring of affection he’s receiving now, another “encore” is in him. If not, we pray he’s comfortable and being well taken care of. BB please accept our love and appreciation.

{Ed Note}This article was written before BB King passed away on the night of

May 14, 2015. May he rest in peace and eternal love from the Blues audience.

The world will never forget his influence on modern music.

'BB King' has no comments

Be the first to comment this post!