INSIDE THIS ISSUE

A long time ago and not so far away I was summoned by the fates to move into an apartment with two male musicians on Norfolk Street in Cambridge, MA. I was going to school at Mass College of Art in Boston and I needed a part time job. There was this bar I had been to, just a few blocks down the street called The Speakeasy and they gave me a job as a waitress and the rest is a story of my love and dedication to the New England blues scene. I got to see, and meet so many musicians, like Junior Wells, James Cotton, Albert Collins and my ultimate favorite Otis Rush.

It was a very busy club. I will never forget one night when Albert Collins took it to the street. There was a long line of people who couldn’t get in, listening and hanging around on the street in front of the club. This was WAY before remote guitar pick-ups, but Albert had a 100 foot cord on his Telecaster and he went all the way outside to play for the people on the sidewalk. (He probably wanted a breath of fresh air too!). Someone had to manage his cord and keep people from stepping on it, it was quite a a difficult operation.

It was so cool when people like James Cotton would come down just to hang out at the Speak. I remember a very young Johnny A would come down to sit in to play blues (he was with Peter Wolf) and Peter Wolf was there when John Lee Hooker played, along with many other musicians who wanted to see the great man. I also remember the buzz about “The Cobras” coming to the Speak, which was Stevie Ray Vaughan’s band at the time.

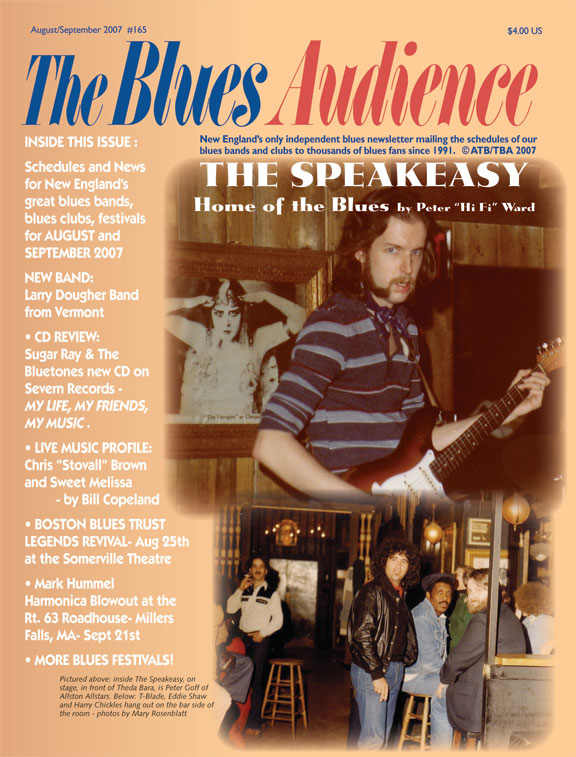

We had such a great time working and hanging out together after the gigs. Paula, myself and Jack, the doorman, Barney, the bartender and Sam, the manager would clean up as fast as we could and we’d go to The Cantab for last call (they were opened ‘till 2pm) and we would all go downstairs and order two huge drinks each and see maybe J.B. Hutto or some other act and of course Joe Cook was upstairs. Peter “Hi Fi” Ward got together with a number of the musicians who played there and Rosie Rosenblatt’s wife Mary had taken some wonderful pictures of his band “Eleventh Hour” and “T-Blade and The Esquires” and Tom Principato contributed the outside shot of Powerhouse with Pierre Beaureguard and Steve Jacobs as long haired “pups.”

Powerhouse Blues band (Tom Principato, Jimmy Cole, Richard Murray, Steve Jacobs and Pierre Beauregard of Powerhouse Blues Band) outside the Speakeasy with that girl that used to finish all the leftover drinks photo by Mary Rosenblatt

Rosy reminded of a night when the 11th Hour guys all piled into my car out in the parking lot, and that was quite a job because it was a two door Saab 96 (the egg shaped kind) and I remember laughing myself weak.

Another funny moment I remember involved Eddie Gorodetsky. He always came in dressed to the nines in a zoot suit or some get up carrying one of those metal suitcases full of 45s and vintage blues albums (I am assuming, I never saw him open it) because he was a DJ. He was also a pretty snazzy dancer. We all jitter bugged back then. He was swinging a lovely young girl in a flowing skirt and I turned around with a try full of empties to see him do a very fancy move where she slid on the floor between his legs and then the idea was to shoot back up with a jump and continue dancing. Well he stepped on her skirt and when she shot back up it stayed on the floor! We all died laughing, she was OK but a they were both little red in the face. A moment etched into my mind forever.

Peter Ward has written a fun article including a number of musicians who played there, and are still playing today. The photos Rosy Rosenblatt and his wife Mary sent me threw me back in time. I remembered the inside of the Speakeasy as black. There were no windows and I never clicked that it was knotty pine and brick! But I do

remembered the little blue booths. Man I saw alot of great musicians there. And that is where I met so many of the local blues bands, many of whom I work with today, including gentlemen like Gary Bernath, Sugar Ray and Rob Nelson and it was at the Speakeasy that I met Ronnie Earl as a very young man. I still have his card that says simply Ronnie Earl Horvath, blues guitar. We were all so stylish back then (and good looking too!).

CENTRAL SQUARE, CAMBRIDGE, MA— It’s where the great traveling bluesman, Robert Jr. Lockwood, one night shyly asked an audience member to go fetch him some Preparation H. It’s where Frank Zappa tried, in front of many people, to hire away a local blues musician, only to be rebuffed — quite publicly. It’s where Robert Johnson’s stepsister revealed the only known photograph of her legendary made-a-deal-with-the Devil stepbrother.

![img209[1]](http://thebluesaudience.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/img2091.jpg)

Frank Zappa- photo by Mary Rosenblatt

“Some clubs may have boasted bigger acts, definitely bigger payrolls,” said pianist Ron Levy, “but this was the place where everyone let their hair down and played musician’s music.”

When it was razed around 1980 to make way for a parking lot, many felt a loss, an injustice. “Some clubs may have boasted bigger acts, definitely bigger payrolls,” said pianist Ron Levy, “but this was the place where everyone let their hair down and played musicians’ music.”

The Speak, as the Norfolk Street pub was lovingly called, gave local blues fans a chance to see a galaxy of blues stars up close. Among those who graced the stage were Hubert Sumlin, Albert Collins, Robert Jr. Lockwood, Jimmy Rogers, Johnny Shines, the two Luther Johnsons — “Guitar Junior” and “The Snake,” J.B. Hutto, Kim Wilson, Jimmie Vaughan, Eddie Kirkland, James Cotton, Eddie Shaw and Koko Taylor.

“That was where I first met Otis Rush — oh my God, way back when he still had that incredible hairdo and wore sharp suits. No cowboy hat back then. I was so taken with him,” said Diana Shonk, a Speakeasy waitress whose passion for blues never wavered. She now publishes The Blues Audience newsletter.

This is the interior of the club. See the “ambiance on the top of the plastic “tiffany” lamps? photo by Mary Rosenblatt

SPEAKEASY PETE

When Peter Kastanos, a former World War II Army lieutenant who received the purple heart and bronze star, opened the Speakeasy with his brother-in-law, Leo Sonis, the timing was right.

BUDDING BLUES MUSICIANS

The Speakeasy also served as a lift-off point for budding luminaries. They included Ron Levy, Rosy Rosenblatt, Dave Maxwell, John Nicholas and the Rhythm Rockers, George Leh, Pierre Beauregard, Donna Rae, Nonie’s Blues Band, Tom Principato, Paul Rishell, Professor Harp, Barbecue Bob, Mike Avery, Duke Robillard, Roomful of Blues, Mark Kazanoff, the Memphis Rockabilly Band, Sarah Brown, Terry Bingham, Mark Cedrone, Babe Pino, Maynard Silva and Sugar Ray and the Bluetones. “Even though I’m a graduate of B.U., the Speakeasy was like my musical college,” said

Ronnie Earl, who spun riffs off his Stratocaster with the Rhythm Rockers and Sugar Ray & the Bluetones.) “It’s where I got to work with all these unbelievable founders of the music — Big Walter Horton, Big Mama Thornton, Roosevelt Sykes, Albert Collins. I saw John Lee Hooker there and the first visit of the Fabulous Thunderbirds,. “People would talk about Antone’s,” said Earl, referring to the legendary club in Austin, Texas. “It was our Antone’s.”

In the 1970s, authentic blues artists from Chicago and elsewhere were still touring, delighted to perform for appreciative baby boomers, many of whom themselves picked up the music and were performing.

Richard “Rosy” Rosenblatt, harmonica ace, was working at the Candlelight Lounge on Western Avenue when a band mate’s girlfriend mentioned a new club in Central Square that might be open to having blues. Pete offered Rosy a one-night audition, which led to five nights the following week. “It was funny because we drew up a little contract and came in with it and Pete laughed in our faces and said, ‘Which one of you kids drew up this thing? I’m not signing this. If I don’t like you after the first night, you’re out of here,’ “ said Rosenblatt. Rosy needn’t have worried. He became a Speakeasy stalwart, working regularly with Billy Colwell, the 11th Hour Band and Allston Allstars.

Eleventh Hour Blues band photo by Mary Rosenblatt

THE SPEAK HAD PERSONALITIES

It didn’t take long for the Speakeasy to develop its own distinct personality. “The place was always full of a diverse crowd of patrons that typically became like family,” said Pete’s daughter, Jaye Clements, 45, of Florida. “White collar to hippies to all kinds of people, and they all got along, just like a regular group of friends. My Dad treated everyone equally. It was pretty funny when the biker crowd took him on as a dad and protected him,” she said. “I mean, these guys really had his back.”

The bartender, Barney, was known for his black leather vest and rapid-fire laugh, and Sam was Pete’s no-nonsense female bar manager.

“Pete and Sam ran a really tight ship, especially given the times and circumstances. All monkey business was conducted in the parking lot — almost never in the inoperable kitchen/dressing room/office which they guarded like it was Fort Knox,” said Levy. Waitressing was handled by a number of young women including Shonk and Paula Zeller, whose exposed midriff and belly button was memorable.

Jack was the doorman here enjoying the show photo by Mary Rosenblatt

BLUES “AMBIENCE”

The Speakeasy was divided lengthwise with the bar and dance floor on one side and booths, tables and stage on the other. The stage had a sign “Home of the Blues,” a plastic Tiffany-style lamp, a clock and that image of silent film star, Theda Bara. “There really wasn’t any décor per se, just your normal working man’s bar-type setup,” said Levy. “The characters frequenting there, as well as the music, provided all the ambience needed of a long forgotten rowdy 50’s roadhouse — misplaced in 1970’s Central Square Cambridge.” [Ed. Note: One night I was wiping down the tables, getting ready for the crowd and I took a rag and went to wipe a deep pile of dust off the “Tiffany” lamps and Pete called out to me, “Don’t do that, you’ll destroy the ambience.”]

The Speak lacked a PA-each band hauled in its own speakers. However, it boasted a pinball machine, hot dog steamer, popcorn machine and a jukebox stocked with rare blues 45s that many fans had never heard before.

To Dave Maxwell, the beat-up piano represented a bygone era. “Clubs like the Speakeasy and Tam O’Shanter [in Brookline] carried upright pianos as a holdover from the way entertainment was before. Usually you had a piano player come into some bar and play background music, pop songs or standards. Seems like every club had a piano in the corner. That changed soon enough,” said Maxwell.

Otis Rush with Kaz Kazanoff photo by Mary Rosenblatt

MUSICIANS DISAPPEAR AT THE SPEAK

In the pre-smoking ban days, the room could swallow up performers. “Sometimes they’d lower the lights way down, and Big Walter (Horton) went halfway down, and Ronnie Earl on stage would say in the mic, ‘I can’t see you, Walter,’ “ said Michael “Mudcat” Ward who played bass with the Bluetones. “And Walter would say in the way he stuttered sometimes, ‘As long as you, as long as you can hear me, it’s OK.’ He played a good portion of a set away from the bandstand. That’s how intimate the club was.”

The stage’s railing had a narrow opening behind the drummer. John Nicholas used it to dramatic effect, making his entrance with his gold Gibson hollow-body ES-295 as he’d launch into a swing number. John Liebman of Nonie’s Blues Band used it differently. On a finale, he put his Stratocaster down, waved to the audience and disappeared through this gap. “At that time, we just relaxed, drank, had fun playing and put out good music,” said Maxwell.

SPEAKEASY PETE KNEW WHAT HE LIKED

Bands occasionally teased Kastanos, who was balding with a big mustache and known for his frugality, but Principato regarded him as a father figure who listened to the music and knew what he liked. “Pete definitely had the passion, because he even talked Powerhouse into doing ‘The Honeydripper.’ That was like his favorite song, and he used to always say, ‘Boy, you guys do The Honeydripper great,’” said Principato. “He even used to encourage me and my lousy singing in those days. ‘You’re not the greatest singer,’ he says, ‘but you’ve got a nasal quality about your voice that’s very appealing.’ So, he had some heart there.”

“Pete gave me $25 for singing lessons once,” laughed Levy, who came off the road with B.B. King and Albert King to play piano with the Rhythm Rockers.

Speakeasy Pete could also be controlling. Some musicians he simply wouldn’t hire. Others he warned against performing in competing venues near his own, which some bands found unwarranted, given the low pay in those days.

“Pete could be a little quirky,” said Principato, “and it turned out, to our surprise, that he needed to approve anyone that wanted to sit in. The first few times we had someone sit in he took us back into the kitchen — into the office — and gave us the old reprimand. (laughs) Actually I have a vivid picture of that because Barney — he was a funny type too — he and Barney would sort of stand with their arms folded in front of them and shake their head and tell you where it was at.”

Paul and Rosy photo by Mary Rosenblatt

T-Blade (of the Esquires) Eddie Shaw and Harry Chickles, Sam the bartender’s brown afro photo by Mary Rosenblatt

BANDS CAME TO BREAK INTO THE NEW ENGLAND BLUES SCENE

Pete would occasionally take a chance on lesser-known bands. “I had given Kim Wilson some contacts in Boston — specifically booking with agent Harry Chickles “The Fabulous Thunderbirds with Jimmie Vaughan played at the Speakeasy in ‘76,” said Bob Margolin, who played guitar with the Boston Blues Band until Muddy Waters hired him in 1973. “I had played tapes of the T-Birds for Tom Principato and he helped spread the word about them. I’m told that when the T-Birds first played at the Speakeasy, the first few tables were full of musicians with cassette recorders.”

LOCAL BANDS AND DIGNITARIES

Steve Berkowitz, known as “T. Blade,” hosted jam sessions, some of which on Mondays were called the Blue Lodge. Eddie Gorodetsky, who would become a Hollywood TV sitcom producer (Two and A Half Men), occasionally did stand-up comedy between sets and promoted blues on his Hi-Fi Party on WERS while Mai Cramer host of Blues After Hours on the WGBH, recorded several shows live.

Unexpected guests dropped by the jams. “One time Frank Zappa was in town, on a Monday night I think. He came up to the bandstand and called off a tune in F sharp, and it really flipped everyone out. ‘F sharp? What the f*** is going on here?’” said Maxwell. Zappa, accompanied by Captain Beefheart and drummer Aynsley Dunbar, played so loud that Tom Principato worried he might damage the Fender amplifier Zappa was using. “After the first song — I went up to Zappa and went, ‘Hey Frank, could you not play my amp on 10?’ Like I tried to be discreet about it, and he went, ‘Oh, I could buy this f****** amp if I wanted to,’ and he put down the guitar and walked away,” said Principato.

Principato recalled a twist. “After Frank stormed off the stage he still hung around and tried to offer a gig to our sax player, Dave Birkin, and Dave turned him down — in front of everybody. Very cool,” said Principato.

People hushed reverently when Mrs. Anderson came to The Speak. She was said to be the stepsister of ultra-legendary Robert Johnson.

“She had a picture of him and showed it to Muddy and he confirmed it,” said Ward, the bassist. “Big Walter played at her table, halfway down the club all while playing and instructing the band. Talking into his mic, he’d say, ‘Give me half a beat ‘cause if you give me a whole beat it’ll deaden me.’”

BANK FLATTENS BLUES HOME

Sadly, the good times were numbered. When the Speakeasy’s lease ran out, the bank next door owned the land on which the tavern stood elected not to renew their lease. Worse, it wanted to level the rambling wooden structure and create more parking for bank customers. “It was sad for everyone,” said Jaye Clements, Pete’s daughter.

Though his bar’s fate was tough to swallow, Pete was undaunted. “It didn’t take him long to open another,” Clements said.

Accompanied by Barney, who still wore his black leather vest, Pete opened the Downtown Lounge in Lowell. One day in 1990, it closed.

Coach, The one the only Speakeasy Pete and Rosy photo by Mary Rosenblatt

Bob Margolin hanging out with Harry Chickles photo by Mary Rosenblatt

SPEAKEASY PETE, GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

In 1991 Pete moved to Sarasota, Florida, where he died, March 7, 2004, at the age of 81. A few years before, Bob Margolin was playing a festival in Sarasota and spotted the former club owner. “It was nice to see him,” Margolin said. “I thanked him for all the good times and good music that so many people enjoyed at the Speakeasy.”

Pete, his mustache now gray, smiled. “He was gracious and friendly,” said Margolin, “and very aware of what a special scene he had hosted.”